Ample Make This Bed

Consequentialism and Sophie’s Choice (1982)

“Don't you see? We are dying. I longed desperately to escape, to pack my bags and flee, but I did not.”

Choices are a very delicate thing.

They bring us joy just as much as they haunt us. They contain the power to instantly change our lives for better or worse. And our choices can enrich or destroy the lives of others. But we always know the consequences of our choices can live with us forever. 1982’s Sophie’s Choice not only brings to life William Styron’s wonderful original novel, but has become so engrained in popular culture as to have passed into common vocabulary as shorthand for an impossibly dissonant choice between two morally abhorrent outcomes.

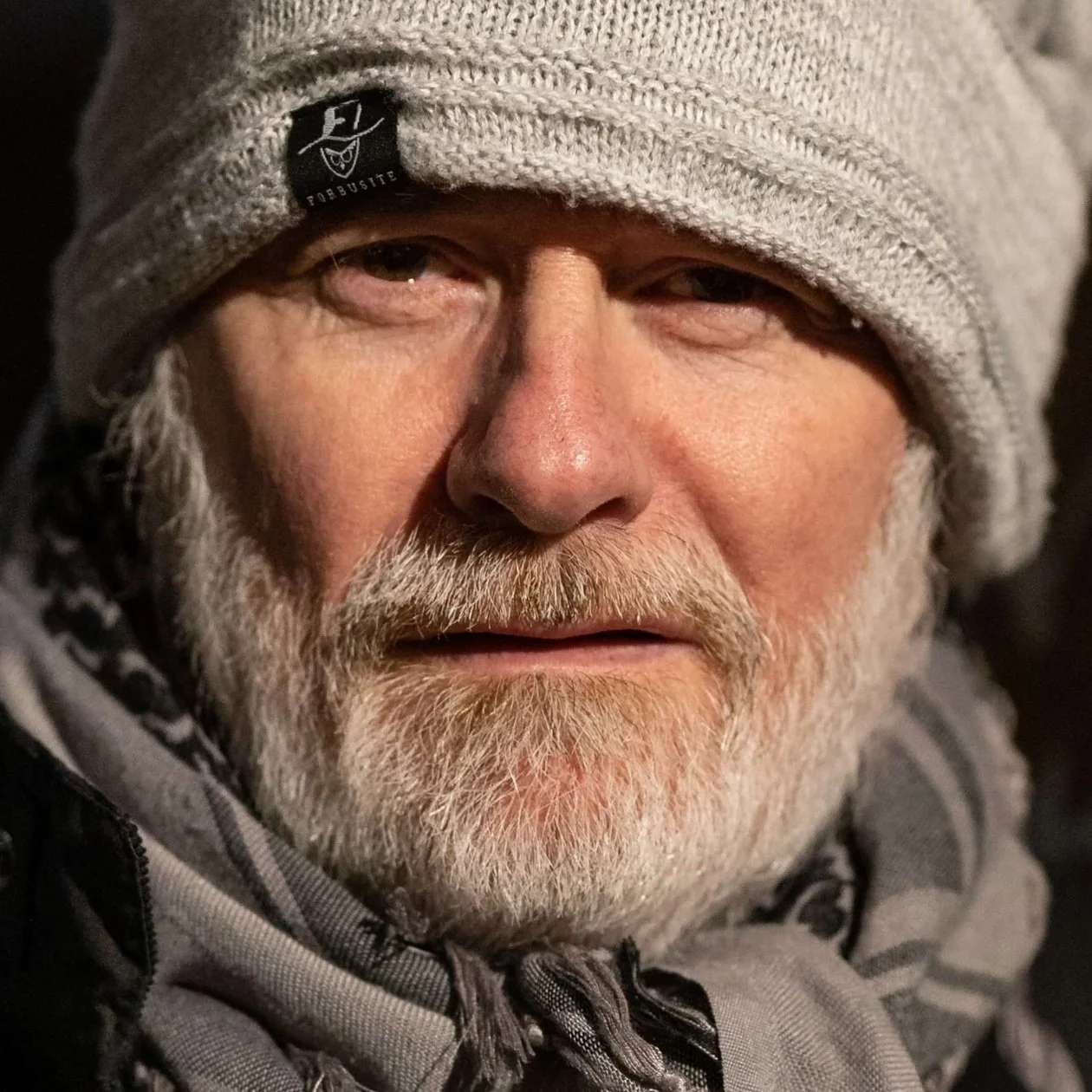

The film is told in retrospect through the narrative of Stingo (wonderfully portrayed with tenderness and sensitivity by Peter MacNichol), a young writer from southern Virginia who moves to a Brooklyn boarding house in the summer of 1947. Here he’s befriended by Sophie (Meryl Streep in Oscar-winning form, she won the Best Actress award for her role), a Polish immigrant finding her way in post-war America. Sophie’s in an abusive relationship with the increasingly unstable Nathan (Kevin Kline in his movie debut), who we first see during an acerbically psychotic violent outburst at Sophie. He swings from tenderness to abuse without warning, and we subsequently discover that he is far from the brilliant biologist he claims to be, but suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and is self-medicating with cocaine. Sophie is drawn back to Nathan no matter what he says or does to her, much to Stingo’s disappointment and confusion, but as the three become increasingly close over a beautiful summer, it’s Stingo, not Nathan, that Sophie confides in to share her story.

“You know, when you... when you live a good life... like a saint... and then you die, that must be what they make you to drink in paradise.”

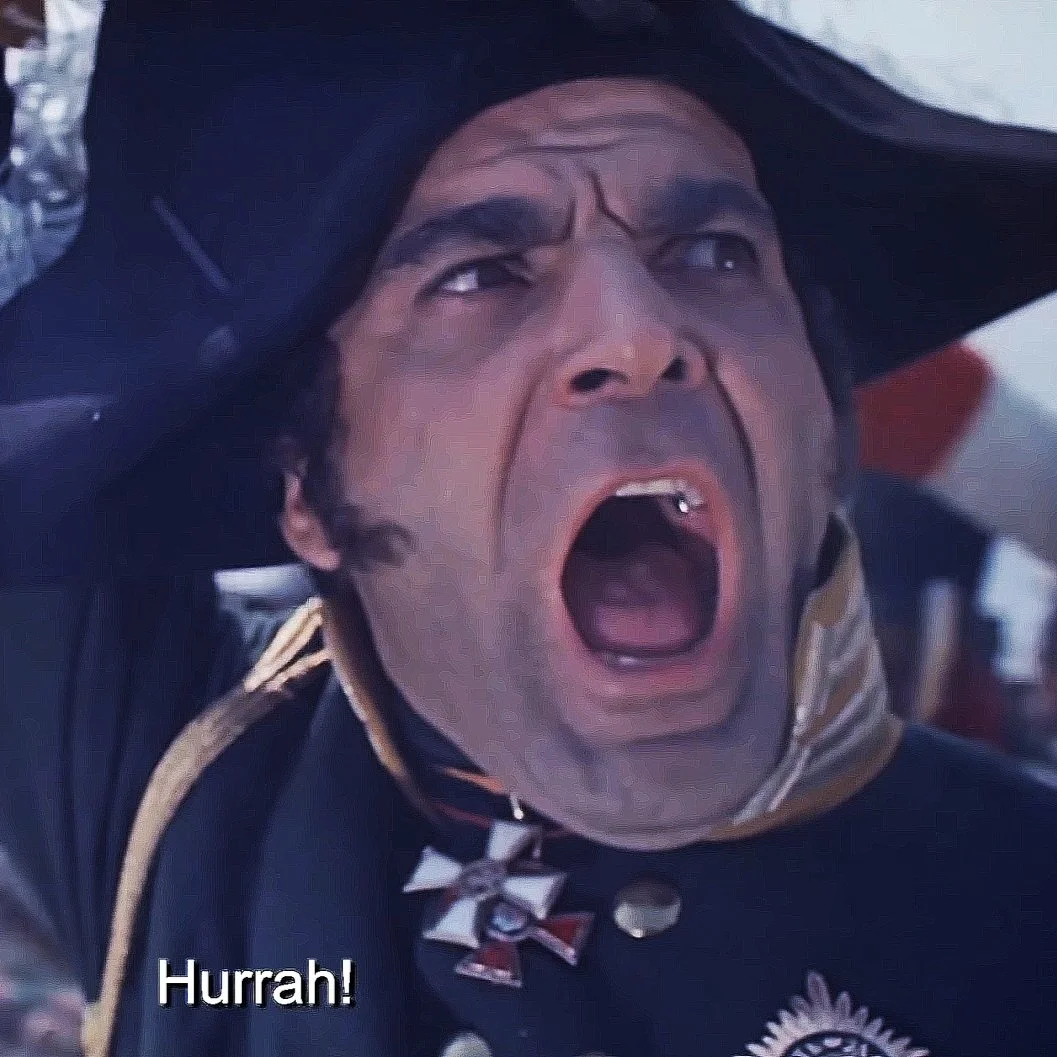

Through Stingo’s recollection, we learn of Sophie’s terrible holocaust past in Poland during the war. Of her father’s anti-semitic sympathies but his execution not as a Jew, but as an academic. We hear Sophie tell of her survival in Auschwitz. How she became a secretary to one of the camp commanders and tried to use her influence to save her son. But we later learn that the story she’s telling Stingo is a fabricated one.

After leaving Nathan for what we believe (and hope) will be the last time, Sophie finally tells Stingo the truth of what happened to her for the first time. How upon arriving at Auschwitz she was forced to choose between her two children. Which would live, and which would die. She repeatedly refuses to choose, but under extreme duress and time constraint chooses her son over her daughter. It’s a sacrificial dilemma that’s a choice within a choice. If she doesn’t choose, they both die. As Stingo pledges his love for Sophie and his desire for marriage and children, Sophie explains to him that he doesn’t understand anything, and pleads with him to stop talking about a future with children.

The two spend the night together, but by morning Sophie’s gone, a tender goodbye note on the pillow explaining that she has to return to Nathan. As the film draws to a close, we find Stingo returning to the Brooklyn boarding house to find that Nathan and Sophie have taken cyanide together, and died peacefully in each other’s embrace.

There’s three distinct moral choices Sophie makes within the film that are worth examining from a consequentialist perspective. Sophie’s choice between her two children, Sophie’s choice to return to Nathan, and Sophie’s rejection of Stingo. All of them draw dramatic and long-lasting consequence for her subsequent well-being, and all of them are far from the utilitarian perspective of maximized good. If we believe consequentialism is the view that the moral worth of an action is determined solely by the goodness or badness of the consequences it produces, Sophie’s choices are all centered around how to minimize the bad, rather than maximize the good, but it’s unclear if there’s any good to be had at all, and we as the audience share the strong cognitive dissonance which defines her life. Her choice, at gunpoint between her two children is an impossible one, guaranteed to be negative sum, as is her choice to return to an abusive relationship, and even her rejection of Stingo, which we feel would be the right choice, just isn’t healthy for her either, much as his ignorant love may seem genuine. Better to be in an abusive relationship than one where the other doesn’t understand you, she feels. In many ways the choice of Nathan over Stingo echoes her choice between her two children. She loves them both, but is forced to make a choice, even though she doesn’t want to.

“The truth does not make it easier to understand, you know. I mean, you think that you find out the truth about me, and then you'll understand me. And then you would forgive me for all those... for all my lies.”

But let’s focus not upon the choices, but the consequences. Her choice between her children not only leads to her daughter’s death, but condemns her to a life of guilt in making the choice at all. Her daughter’s final moments are in the knowledge that her mother didn’t choose her. Her choice to return to Nathan ultimately leads to double suicide and the emotional scarring of Stingo. And her rejection of Stingo leads to heartbreak for him and the missing out on what we imagine might be future happiness for both of them. There’s very little hedonistic outcome in any of these consequences, no-one’s well-being is improved, and no-one willingly wants to make such choices. In many ways her life is punctuated with awful consequentialist dilemmas where, as the audience, it is impossible for us to empathize.

We cannot feel anything other than shared intense anguish at her having to choose between her children, and in constructing this cognitive theory of Sophie’s mental state, we feel it swiftly, automatically, and intensely. We feel all the emotional experiences which arise from negative valence and high arousal, such as fear, contempt, disgust and anger. The result is that as we express this compassion for her, we actively try to take her perspective, and we attempt to share her emotions. How successful we ultimately are is questionable because (thankfully) we are so unlikely to have ever experienced such a thing in life. This kind of cinematic empathizing is painful, consciously so, and we feel the visceral guilt Sophie feels as her daughter is taken away in tears. We feel the gravitational pull of wanting to help, but of course, never can.

“I don’t see any point in trying to equate one evil with another, or to assign some stupid scale of values. They’re both awful!”

In many ways Sophie becomes the single identifiable victim, where we will respond with greater urgency to help them compared to a larger, more amorphous group with similar needs. Indeed, the thousands of others also waiting on the cold Auschwitz platform to be sorted are nameless, faceless extras with no dialogue and no motivation for us to care at all. They are literally background filler, even though they are in the same sacrificial predicament as Sophie. Unlike her, they are outside of our moral circle, and have no opportunity to enter into our moral orbits. We do not know them. We do not hear them. The only patiency we feel is Sophie’s, and if we were to apply the sacrificial dilemma of the trolley problem here, there’s an equality between both lines the trolley could be diverted towards. There is no ‘greater good’ if both outcomes are equally terrible. The only way out of it for Sophie is to ensure that at least both children don’t die, which they eventually do anyway, with the son never making it out of the camp. If utilitarianism demands impartiality for the good of aggregate welfare, Sophie’s choice, in forcing her to be highly partial, can only produce suffering. Therefore, if we think of partiality as a traditional source of pleasure for us, what Sophie endures is being asked to be partial to family members to which she is highly impartial. But in making such a partial decision, it causes guilt from which she can never escape.

“Then I resolved that I would go back out there and somehow cope with the situation, despite the fact that I lacked a strategy and was frightened to the pit of my being.”

If Sophie’s being asked to be partial in the extreme, the utilitarian choice she faces is the inverse of impartial beneficence, and a clear demonstration of maximized instrumental harm. She must choose a favorite, and in doing so, she must harm the other in the extreme. But if the best action is simply the one which produces the greatest overall wellbeing, and if that requires harming a person or group as a means to that end, that is, harming someone for instrumental reasons, then we believe such an action is morally good. But here there simply is no ‘greatest overall wellbeing’ other than ‘at least one of them stays alive instead of both of them dying’.

But through it all we still believe Sophie to be a morally good person. We experience strong resonant affective empathy with her at the hands of Nathan’s abuse from the very beginning. We feel her linguistic and cultural struggles to adapt to modern America. And we know that she is filled with love, despite what life has given her. So in this sense, irrespective of the awfulness she’s endured, through it all she has still endeavored to do the right thing, and we admire her for it. Through kindness, charity, love, resilience, determination and generosity, we want the truly deserved eudaemonic happiness for her. But it never comes in the way we intend. She dies peacefully in Nathan’s arms, and perhaps this is eudaemonic happiness for her. To finally be at peace and free from future consequence.

Sophie’s Choice offers us an fascinating perspective on utilitarian and consequentialist thinking, by offering up not just a decision between which is the greater good and seeking to maximize welfare, but by offering a choice between two things that are morally equal, and forcing a knowingly terrible consequence. An environment where there is no seemingly good outcome. In the end, Sophie chooses to let her daughter die, rather than her son and daughter die, and the consequence of that forced outcome lives with her forever as guilt and the inability to form close relationships. Even when she is offered the promise of happiness, she rejects it in favor of a life of continued abuse. Her happiness finally comes in the form of no longer having to make any choices. To finally be free of the need to make judgments and decisions. And as the close of the film fittingly describes, “This was not judgment day. Only morning. Morning, excellent and fair.”

Sophie’s Choice is currently streaming on Amazon Prime.