Why Social Media Is Making Us Miserable

RETSO Real Estate Conference Keynote, Atlanta 2012

Programming Note: I miss Atlanta’s RETSO conference. I only went twice, both times as a speaker, but it was easily one of the best real estate conferences I ever attended. Exceptionally well organized, and predicated on small, meaningful, genuinely helpful sessions, it had a sprit of non-commercial kindness running through it that’s very rare, especially for sales-based events. This presentation was the first time I’d ever been a main keynote speaker, and it was a tremendous amount of fun not just to put together, but also to share with the audience. I remember being very nervous in the green room beforehand, and feeling an enormous sense of relief afterwards. Later that evening, I celebrated and had one of the best times ever at Happy Karaoke.

Hello everyone, today I’m going to read you a story.

Why’s that? Because I believe that storytelling is at the heart of communities, families and cultures. It’s also at the heart of memories. It’s the most shareable type of content that has ever existed, on or offline. And as a digital marketer, especially in New York, I believe it’s in the DNA of what it feels like to own a home.

I’m going to share with you a series of case studies from all over the world, developed and shared by digital marketers, physicians, economists and psychiatrists, on the impact our current device and media driven existence is having upon us all. If you buy into the idea that the web is moving swiftly from collections of pages, towards conversations and sharing between people, then in order to capture people’s interest and attention, I believe you need to fundamentally understand how the brain works. This is becoming a critical skill of differentiation for digital marketers to understand and leverage. If we want to understand how people influence each other and make decisions, share things amongst themselves, and talk favorably about what we as realtors do, then we need to focus our efforts on the relationships between people, instead of people themselves. I believe this idea holds the future of our industry’s online marketing.

I’m going to question some practices which you thought might be helping your customers, but aren’t.

I’m going to attack multitasking.

And perhaps most importantly, I’m going to provide a glimpse into the future of homebuyers, and show you what’s really happening to our brains on social media.

But at the heart of my story, is a message about customer service and remaining visible.

But before we get to all that, I want to share the story of a 15 year old Korean boy named Lee Chang-Hoon. Here’s Lee. Lee currently attends The Jump-Up Internet Rescue School in Mokcheon in South Korea, a government-funded digital addiction facility which is part boot-camp, part rehabilitation center and focused on building emotional connections in the real world, while weakening those in virtual worlds behind screens. It provides exercise, outdoor pursuits such as rock-climbing and horse-riding, and attempts to provide a rich, healthy lifestyle, disconnected from the web.

According to a fascinating story in The New York Times, “South Korea has built over 150 internet addiction centers, and implemented similar programs in over 75% of their hospitals, where compulsive internet use has now been identified as a serious mental health issue. In a country with over 90% broadband penetration (that’s almost twice what it is here), and where the web is far more ubiquitous in people’s lives, the issue of universal web access has become an acute problem. As aggressively as the country has adopted the web, it’s now finding the need to address the consequences just as swiftly.”

Attendees of The Jump Up Internet Rescue School usually suffer from a consistent combination of ailments. Simply put, it’s the inability to stop using a computer. High levels of screen tolerance (built up over years of practice), are causing severe withdrawal symptoms such as anger, craving and even violence when expressly prohibited from logging on. I think that some of you who’ve ever lost your iPhone know what I’m talking about here.

Lee began using the computer to pass the time while his parents were working, and he was home alone. He says he quickly came to prefer the virtual world, where he seemed to enjoy more success and popularity than in the real one. Sound familiar? At its peak, he spent 17 hours a day online, mostly looking at comic books and playing role-playing games. He played all night, and skipped school two or three times a week to catch up on sleep. When his parents told him he had to go to school, he ended up reacting violently.

“He didn’t seem to be able to control himself,” says his mother. “He used to be so passionate about his favorite subjects at school. Now, he gives up easily and gets even more absorbed in his games.”

Lee was reluctant to give up his pastime.

“I don’t have a problem” he said in an interview three days after starting the camp. “Seventeen hours a day online is just fine.” But later that day, he seemed to start changing his mind, sort of.

During one of the outdoor activity sessions, a drill instructor barked orders at the boys.

Lee climbed up the first obstacle, a telephone pole with small metal rungs. At the top, he slowly stood up, legs quaking, arms outstretched for balance. Below, the other boys held a safety rope, attached to a harness on his chest.

“Do you have anything to tell your mother?” the drill instructor shouted.

“No!” Lee yelled back.

“Tell your mother you love her!” ordered the instructor.

“I love you, my parents!”

“Then jump!” ordered the instructor.

Lee squatted and leapt to a nearby trapeze, catching it in his hands.

Later, Lee mentioned the experience had been more thrilling than the games he was used to playing online.

Thrilling enough to wean him from the Internet? Not quite.

”I’m not thinking about games now, so maybe this will help. From now on, maybe I’ll just spend five hours a day online.”

Lee’s example isn’t an isolated case, and recent research into the media consumption habits of American teenagers reveals some very similar, but embryonic patterns. Remember, while from typical, these are the current habits of first time home buyers in 5-10 years time.

On average, with almost 11 hours of media consumption each day, primary focused on TV, music and the web, American teenagers are now spending more time on screens and devices than they are on sleep. This represents a four-hour increase over the past 10 years, and the first time this metric has surpassed the recommended sleep average.

Similarly, if they’re using mobile devices (and I include tablets in that category), they spend an extra 30 minutes more versus non-mobile users. The average American teenager sends or receives 75 text messages a day.

And of course, there’s no need to delve further into the growing sense of digital overload as that’s well documented online (interestingly enough by those arguing against contributing further to the noise), but the idea that we’re now absorbing 3 times as much information each day as people did in 1960 is a firm reality, with few signs of slowing down.

But, as the volume of information has increased, our brains’ capacity to process it has not kept pace.

So, as opposed to exploring how the speed of content creation is increasing, I believe a more effective area to explore is what’s exactly happening to people’s behavior, as they consume this increasing firehose of information.

What’s happening to attention spans, behaviors, and consumption habits? Let’s take the main offender in the rogue’s gallery of digital overload, e-mail. Recent studies on how people use email on desktop computers during the work day found that, on average, the amount of times people checked their email or changed windows between tasks was 37 times per hour. That’s about once every 90 seconds. More on email later.

Many advocate the idea of multitasking under the guise of increased and more effective productivity, but what I propose, and what neurological data is slowly beginning to support, is that forcing the brain to jump back and forth between simultaneous streams of thought leads to stress, the inability to think creatively, the inability to problem solve, and ultimately, slower response time and ever worsening decisions. If you pride yourself on customer service, multitasking is your brain’s enemy. Our efforts to do more are making us stupider.

Let’s look at a specific example. Dr. Marcel Just, a cognitive psychologist at Carnegie Mellon University tested the brain’s ability to do two things at once.

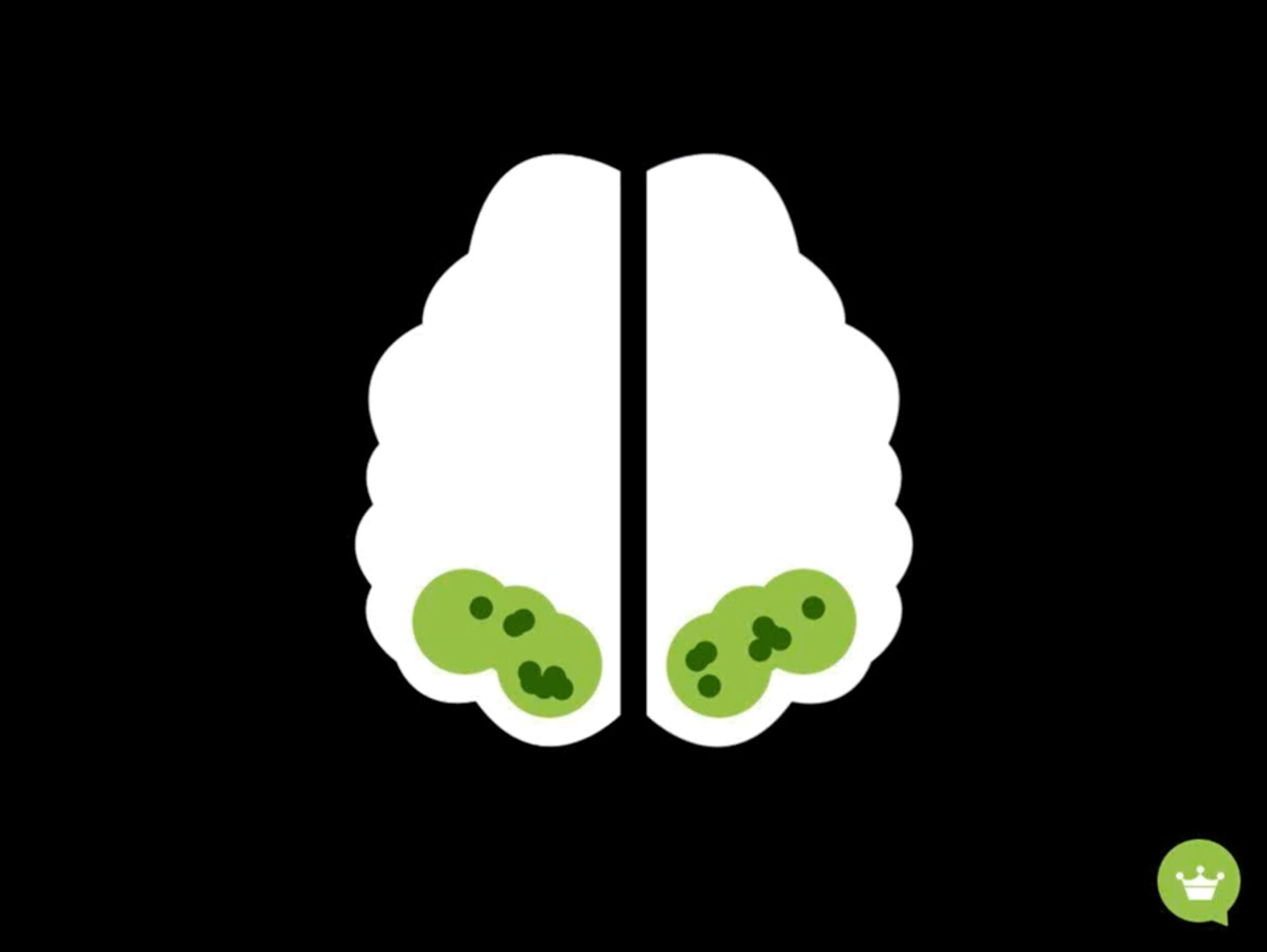

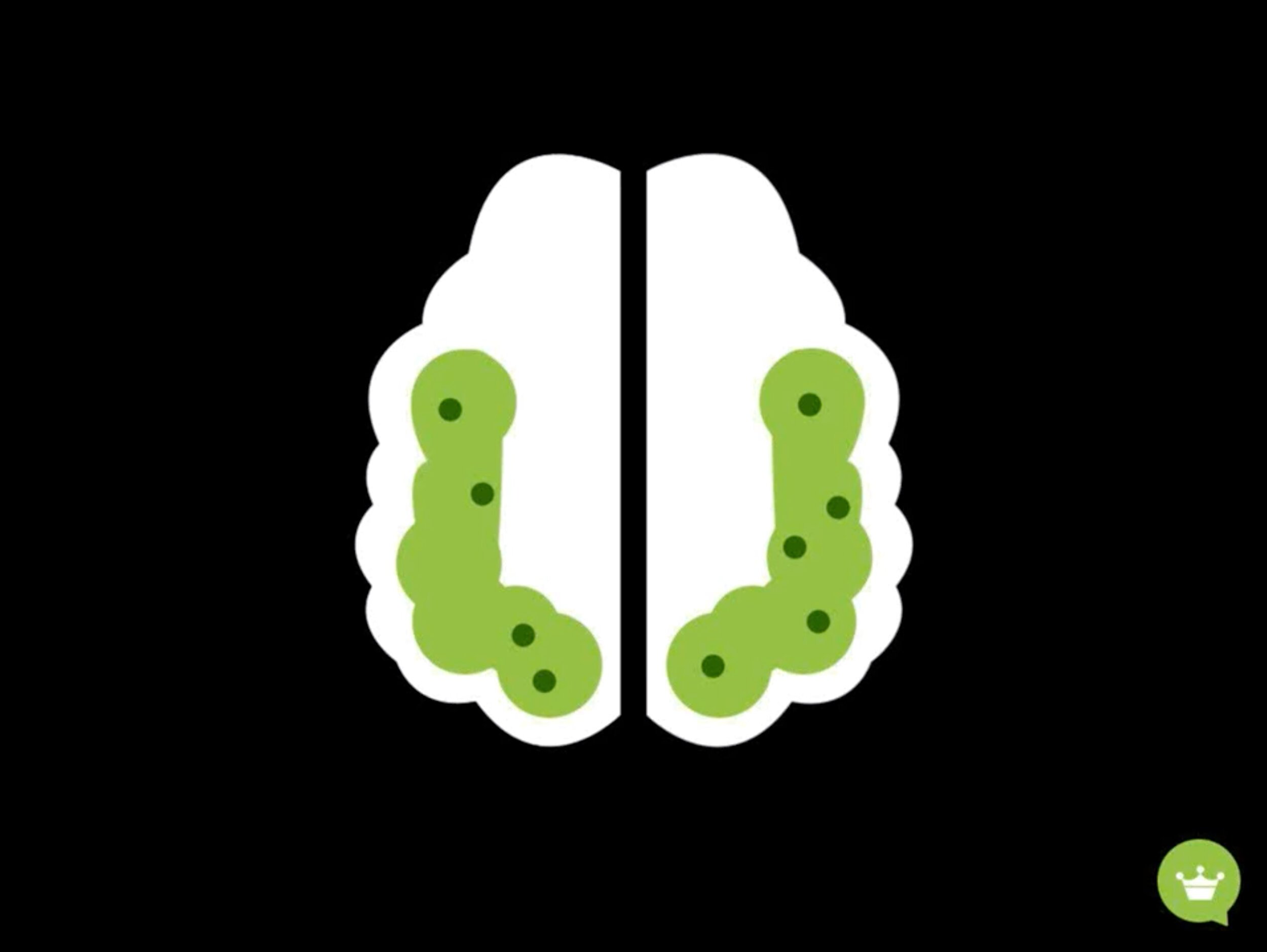

Here’s the first test, where the person was asked to do one thing. In this case it was listening to complex sentences and then answering true or false questions. This is called a language comprehension task. The dark green areas indicate where brain activity is happening, here we see it in the temporal lobes, those areas of the brain focused on semantics, listening, speech and vision. It’s also the places where memories are formed. So if you believe that memories provide the most shareable type of online content, then this is a good place to look.

Now let’s look at another more physically-based cognitive task. Subjects had to compare pairs of three dimensional objects and mentally rotate them to see if they were the same. This is referred to as an object rotation task. So if I asked you to picture two spinning cubes, that’s the example being used here, and what you’re doing right now. Again we see strong brain activity in the temporal lobes.

Now let’s look at both together, where the person was asked to multitask. We see activity again in both areas consistently, but overall the brain’s activity has significantly dropped.

French scientists Slyvain Charron and Etienne Koelich have also discovered that our brains struggle to process attention across more than two tasks at any given time, so when you think you might be multitasking, what your brain is actually doing is rapidly skipping from task to task, not focusing on any on thing for any significant time. This is what’s referred to as cognitive dissonance. It’s brain noise.

While on the one hand, these incremental changes in our ability to rapidly process data are causing IQ levels to rise globally as information spreads more rapidly online, when multitasking, Charron and Koelich’s findings illustrate that each half of the brain focuses on different goals with an overall drop in performance, and notably without the capacity to process three things at once.

Is multitasking, especially in a digital environment, ultimately making us slower and less able to think? As we skip happily from social platform to social platform, liking, sharing, plus-one-ing and tweeting, are we being more productive, or actually inhibiting our ability to think coherently and creatively? What does this do to how we work with clients? The key word here is actually happily, and the emerging field of neuroeconomics has a huge interest in what’s actually making us tick.

For many of us, we now have more digital relationships than real-world ones, and the maintenance and management of each of those ties can often outweigh the ability to perform the most trivial of tasks, such as eating dinner in a focused way, or watching a movie. Time with friends is shifting to mean something different.

Many take the idea of an Internet Sabbath to heart in order to recharge and connect with their real-world ties such as friends and family.

A new restaurant game is emerging where people stack their iPhones together in the middle of the table in front of them. First one to touch the phone pays for everyone.

The need to check our Facebook and Twitter streams has become a compulsion, especially in the era of ‘always-on’ mobile technology, and some compelling new research into the long-term chemical implications of what these networks are doing not only to our brains but also our minds is now starting to be published.

Neuroeconomics - combining biology, neuroscience and psychology is beginning to provide some fascinating insights into chemical relationships between what a person is doing at a particular time (especially online), and the specific release of certain chemicals into the brain, impacting wide-reaching ideas around empathy and generosity. Many organizations are beginning to experiment with understanding the results of this research from an economic perspective, deepening their understanding of what neuroeconomist Paul Zak terms ‘the understanding of human beings as economic animals’.

Is there a chemical relationship between emotional reactions, behaviors, relationships and using the web? Zak’s research leads us to think so. Having undergone an extensive series of MRI-based tests (just like the ones I showed you earlier), focused on measuring specific chemical release patterns when people are using platforms such as Twitter or Facebook, Zak suggests that ‘social networking triggers the release of the generosity-trust chemical into our brains’. The brain is experiencing social media as if it was the same as a real-world interaction, associating a synthetic ‘essence’ of offline affection, by releasing what he calls ‘the cuddle chemical’, otherwise known as Oxytocin (importantly not to be confused with the painkiller Oxycontin).

Oxytocin, interestingly, is also found to be the hormone released between mothers and babies that forges bonds between newborns, and at scale, Zak describes this chemical as a type of ‘social glue’ or even ‘economic lubricant’ adhering families, communities and societies through the building of trust.

Oxytocin, as a chemical driving issues of generosity, empathy and sharing, is one way that Zak’s team is beginning to concretely visualize the mechanisms that drive specific types of human behavior. The impact of the brain’s chemical release of Oxytocin patterns as triggered by emotional ‘warmth’, border on the cynical when applied to economic behavior at scale, but the primary conclusion that it’s released by having emotionally-driven contact with others, specifically touch (even if it’s virtual), is measurable, and producing real-world results.

Studies performed by Zak’s team have attempted to answer the question of how social networking impacts the release of oxytocin into the brain. One such test performed over a ten-minute span monitoring someone using Tweetdeck, without specific reference to anything special happening in their feed (they were just checking their news feed, and responding to minor, stress-free conversations), saw a 13.2% spike in their levels of oxytocin, and they also saw the number of stress-related hormones in their body significantly reduce. The use of social media produced a calming, soothing, pleasurable effect that was chemically measurable in their brain.

They felt good using Twitter. Perhaps this is why millions of people use these platforms — our brain simply feels good on them.

In other tests, people artificially given oxytocin over time, gave 48% more to charity over those administered with a placebo. Overall, the higher the levels of oxytocin in the body, as generated by emotional activity and the use of social media, the more reciprocal and generous the test subjects became. So, it’s no wonder that the buttons are called ‘Like’ and ‘Share’. It’s a cycle that promotes use of the networks, makes us feel good, and most importantly, keeps us using them all day. The key metric that the majority of Facebook users return multiple times during the day to ‘check in’, speaks to a classic need to emotionally connect with our digital friends, and perpetually refuel on the release of oxytocin.

Zak goes further, proposing that this same research, adopted at scale, can be a concrete driver of economic development. He suggests that the deliberate creation of emotional experiences aimed at elevating levels of oxytocin in the body will build communities of the most generous, loyal, passionate customers. Sound familiar?

Given what we see as the most ‘shareable’ types of content across Facebook being empathetic, human-interest driven, visual storytelling, it’s hard to disagree with him. That type of content specifically releases a type of chemical into our brains which makes us more inclined to share it, and the more we do this, the more we want to do this.

Perhaps this is one way to understand the primitive science behind how Zuckerberg’s Law (which suggests that the amount of content shared online doubles every 10-12 months) continues with such aggressive growth. Zak argues that societies with higher levels of trust have higher incomes, more stable governments, and the greater the number of positive interactions between people, the greater the acceleration of economic prosperity.

It’s a stretch, but he ties it to the specific release of chemicals into the brain, across entire communities.

However, one question that comes as a result of this research, is that with greater and greater levels of oxytocin being released into our brains every day as a direct result of the increased and aggressive adoption of social media, does it create a compulsive need for constant connectivity? A need to continue the regular release of those ‘feel good’ hormones into our bodies? However synthetic, electronic connections are being processed as real-world connections in our brains. With no relation to the physical proximity of those people in the real world, what does that do to brains over time, especially those growing up in an environment where social media is omnipresent?

One such counter-perspective comes from Baroness Susan Greenfield, Professor of Synaptic Pharmacology at Oxford University, who argues that the need for constant connectivity and connection, produces increasingly short attention spans, a compromised ability to actually empathize, and results in a shaky sense of real-world identity as fueled by social media, creating what she terms an ‘infantilizing’ of the human mind. This is what we saw earlier with our friend Lee. She argues that because real-world experiences are inherently slower than online ones, especially the ability to process multiple streams of information across multiple networks, what results is a heightened increase in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (or ADHD).

More importantly, the validation of these social experiences, their impact on learning, and the lack of consequence associated with them are creating ‘a generation defining themselves exclusively by the responses of others’. How often have we heard that same advice applied to brands and personal presence on social platforms?

One of the biggest aspects of our lives impacted by a growing climate of external validation and chronic information overload is, of course, how we learn. If the brain is being fundamentally and chemically changed by our daily use of these social networking platforms, and we’re getting smarter and smarter at filtering, editing, and refining our own attention spans (just think of how you react to and retain information about advertising messages these days), how do we retain the necessary information required to learn, grow and master the things we actually need?

While social media advocates promote the notion that this new improved capability to multitask as never before creates new paths of discovery and interactivity in the brain, is that actually true and does that really happen? What we’re talking about here is how customers learn and retain information.

Traditionally, social interaction has guided people’s ability to learn (people sharing things with us), but does it actually stimulate brain activity? Do we retain more information if we’re undergoing that process as part of a group rather than passive one-way learning through simply listening, or sat in front of our desktops?

Further studies on infant brains have shown that knowledge retention is only truly possible for the long-term when accompanied with personal interaction, an aspect that becomes a lot more important as we age. The findings conclude that adults must somehow be socially stimulated in order to learn at all, and the idea of manufacturing cognitive flexibility becomes an interesting one to consider.

Think about this next time you wake up in the morning. What percentage of the content you think you consumed online yesterday are you actually capturing and retaining? How much of it can you actually recall, and how specific can you be with it? How much of your content is genuinely retained by others? For many of you, that might be a real challenge.

A lot of the criticism aimed towards a diminished ability to be able to learn, is currently being directed towards an omnipresent screen-based culture. Something fueled by social media and a growing mobile culture of apps which promotes the notion of what’s described as associative skipping — moving rapidly from topic to topic, with less linear and limited retention of any palpable or relevant information. With multiple sources competing for our attention throughout the day, the ability to focus is becoming a premium commodity, and even when we do achieve the much sought-after ‘downtime’, it’s often still spent with something screen-based — a movie, iPhones, the TV, or our much beloved iPads.

To paraphrase Seth Godin’s Purple Cow example, in order to even attract our attention at all, these media experiences have to be truly remarkable. How remarkable are yours? How remarkable do people find your presence on social media platforms?

iPads in particular have come in for some strong criticism in directly impacting sleep habits, especially amongst those users who read with them before bedtime. Because they use a display which emits light (as opposed to the Kindle model of e-Paper, something that can be read in direct sunlight), having prolonged exposure to this kind of abnormal light source, especially positioned close to one’s face, inhibits the secretion of melatonin, the chemical the brain needs to shut down for the evening. Melatonin is usually produced in response to darkness, and these screens send artificial messages to the brain encouraging it to stay alert, a set of messages only amplified by the screen’s proximity to our faces. As screens get smaller, we have to hold them closer.

And, as we hold smaller screens to our faces, and the degree to which we begin to live our virtual lives through mobile technology, the well-documented issue of eye strain obviously comes into play as well. Even when we’re resting, there’s usually a screen involved in our leisure time.

Obviously a reduction in the amount of ‘screen time’ prior to going to sleep is optimal, but that’s an increasing struggle for many, in a culture of ‘always on’ social media. Many of us still wake to the ping of incoming messages, and the blinking, flashing light of alerts on devices left by the bedside. We’ve willingly subjected ourselves to the tyranny of the digital alert. If you have the truly noble goal of responding to each and every person who reaches out to you with a ‘no interaction left behind’ working perspective, can this actually be achieved at scale, and what kinds of chemical changes are you asking of your brain to accomplish this?

The field of research into changing brain patterns based on our increasingly umbilical devotion to social media platforms is still very much in its infancy, but will be a fascinating one to keep an eye on into the future, and I highly recommend it’s something your marketers look at. These types of conversations build stronger marketers. Just as the pace of technological change is heralding incredible changes in connectivity, productivity and information exchange, so our brains may be undergoing similar physical changes in order to accommodate even the smallest capacity for coping with what’s happening.

Paul Adams, in his wonderful book Grouped, describes a critical shift in understanding how the web is forcing us to think about consumer behavior. The classic sales funnel is based on linear, rational thought, with the customer progressing towards conversion in a structured way.

Working with funnels is predicated on customers making rational decisions. But they don’t.

Most behavior, especially decision-making, is driven by our non-conscious brain, which is why most of us, more often than not, can’t explain why we do the things we do. If our past experiences drive our patterns of behavior, which are then stored as parallel neurological patterns in the brain, then new and unexpected things, things that don’t fit the pattern, capture our attention. It might be time to do something different.

Indeed, Adams suggests that neurological research is finding that our brains are craving such experiences. However, this isn’t an excuse to practice more and more interruption marketing, that isn’t what we’re talking about here, as the unexpected experience can often be a negative one, and interruption marketing is basically a race to the bottom of the web. If, as Adams proposes, we make most of our decisions using the non-conscious brain, then appealing to the customer’s rational brain with facts, figures and concrete information is actually the wrong approach. People buy just as much with their hearts as their heads, and for many of you in this room, it’s time to rethink how you use data.

Pushing more and more data at what you perceive to be your online audience actually runs the risk of creating cognitive burnout in the minds of those same people you’re trying to reach. I argue that this is why all of the large real estate portals are more about searching listings, instead of finding homes. It’s not about data, it’s about answering the fundamental question the customer has — ‘what does it feel like to live there?’

Indeed, as organizations begin to experience more symptomatic fallout from stress-related digital burnout, some of the them are already beginning to adapt to changes in behaviors they’re unwittingly asking of their workforce, deliberately forcing their employees to switch off and create more of a work and life balance.

Sensitive to the disruptive influence of the digital alert, Volkswagon in Germany are one of the first to implement such electronic communication for their team. 30 minutes after their shift ends, the company stops emails being sent or received from their internal servers, essentially blocking access to email and taking the employee offline in the work sense. The service is restored 30 minutes before the work day starts the next day.

With employee burnout, fueled by the lack of digital downtime, becoming a growing mental health problem in Germany, Volkswagon are attempting to balance the benefits of round the clock access with protecting and supporting the private lives of their employees. It’s a difficult productivity line to walk.

Now that we live in a state of near permanent distraction, universal connectivity simultaneously aids and hinders productivity. As I mentioned before, the absence of digital activity, the empty inbox, the lack of likes or retweets, triggers feelings of anxiety and compounds feelings of emotional bankruptcy, fueled by the release (or not) of oxytocin.

Email appears to be at the heart of many discussions around this problem. Email is incredibly effective at diffusing concentration.

Atos, a French technology company, plans to eliminate all internal email by 2014. Why? A survey of their 80,000 employees found that on average they were each receiving over 100 internal emails a day, where only 15% of them were relevant to actual work. Similarly, Henkel (the makers of such products as Loctite Glue and Right Guard Anti-Perspirant) declared an email amnesty between Christmas and New Year in 2011.

One interesting case of employee burnout happened in early 2011, with the stress-induced absence for a couple of months of António Horta-Osório, the CEO of Lloyds Bank. Sir Win Bischoff, the Lloyds chairman, said he had an ‘inability to switch off’.

Inability to switch off (or ITSO) is what New York Times writer Roger Cohen calls a ‘modern curse’.

Horta-Osório has said he made the decision after not sleeping for five days in late October, and realizing that there was, according to his doctor, such a thing as getting close to the end of your battery (an interesting choice of words). He’s now been pronounced fit by the Lloyds board, but has said he will change his work habits, presumably in ways that will lower the risk of needing to switch off, before his body flips the switch again for him.

So, given this climate of increasing digital burnout, at the expense of one’s health, how do we, as digital marketers, agents and real estate professionals serve the customer better?

A recent study by researchers at University College, London, called out some seismic shifts in even the simplest online tasks, such as the ability to read. They conclude that “It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed there are signs that new forms of “reading” are emerging, as users “power browse” horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.” Anyone familiar with the technique of linkbait-driven headlines will be familiar with this approach. But as reading and consumption habits change, how might we future-proof our marketing?

British travel writer Pico Iyer suggests that the key to marketing to next generation consumers lies in the importance and exclusivity of stillness and digital downtime. He suggests that there is increasing value in being able to escape from the time-saving devices we so readily embraced in the past, so much so that ‘Black Hole’ resorts, those with no internet access, and that force communicative disconnection, are becoming luxury items. Indeed, to economists, if luxury is a function of scarcity, and if web access is universal, then downtime becomes a highly sought after commodity.

This is the Post Ranch Inn in Big Sur, California, consistently rated one of the world’s best hotels.

It’s a boutique hotel with a unique twist. Guests here pay well over $2,000 a night for the privilege of not having a TV or web access in their rooms. Digital downtime is something many are willing to pay for, and a vacation from the web, enforced stillness, and isolation from technology is fast becoming something luxury resort hotels offer their guests. Similar programs are rolling out across the country, with the Sheraton Chicago even offering a ‘Blackberry Detox’ service to its guests, which says if you can go 48 hours without the need to check your device (they lock it away in their vault), you get a free night’s stay and a steak dinner.

And it’s easy to understand what we’re taking a vacation from. Nicholas Carr, author of ‘The Shallows: What The Internet Is Doing to Our Brain’ found that during a normal week day, the average American spends 8.5 hours a day in front of a screen, with the poor office worker enjoying no more than three uninterrupted minutes at their desk at anyone time.

Even when we get home, the volume of dual screen simultaneous use is rising as we chat to our friends about American Idol while we both watch along on TV. Unfortunately, we have more ways to communicate than ever before, but less and less to say, simply because all we’re doing is responding all the time. It’s time to change that.

But after spending time in quiet, rural settings, Carr found that people ‘exhibit greater attentiveness, stronger memory and generally improved cognition. Their brains became both calmer and sharper’. With an estimated 9 million Americans at risk of pathological computer use, it seems there are surprising benefits of solitude, allowing the brain to recharge and recover from the digital gymnasium it spars in every day. In an era of ubiquitous web access, this is how your brain helps you become a smarter agent.

Anyone looking to capture attention and interest in the mind of the consumer needs to rely on the relationships between people, and not the details of what’s being shared or the component parts of people’s behavior. Unlike news websites, it is not in our economic interests to further drive online users to distraction.

We need to have a deep understanding of how what we do, makes people feel.

In an era where simply too much information is being pushed at us, if most of our behavior is driven by ruthlessly edited, pleasure-seeking, emotional decision making, then appealing to emotions instead of rational thought is not only the way to remain visible and relevant, but also creates magical experiences for your customers.

Now, like all good marketers, I need to close with a call to action, so I ask of you. Will a golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom spring from our hyperactive, data-stoked minds? Time will tell, but I call on all of you today, to use these data points, these stories, and these ideas to create the future of the real estate industry’s marketing. I appeal to all of you to believe in your own ability to create exceptional digital experiences, to shift gears, and to have fun.

I believe in everyone in this room’s ability to affect incredible, beautiful, meaningful change for our industry. Because the answers to our industry’s dissonance, disintermediation and discord, and truly the way to instill confidence IN the mind of the consumer, is to focus ON the mind of the consumer.

I believe the answers to these questions are in this room today.

Anyone involved in building products, especially those centered around homes, needs to understand social behavior, networks, and ultimately how people think when they use the web. And most importantly, my message to you is that life ISN’T a sequence of waiting for things to be done.

Doers win, every time. Let’s get to work.

I hope you enjoyed my story.

A few weeks later, this presentation was also presented in Spanish as a real estate webinar by Fernando Garcia in Barcelona. Fernando had been in the audience at RETSO, and wanted to bring the presentation to a Spanish audience, so he used the same slides, and spoke to each of them based on notes he’d taken during the original talk. So interesting to see the work travel into a different language.